So those bikey bike posts that I wrote a couple of weeks ago were supposed to just be a setup to a new Uganda post. I had a couple more little odds and ends from Uganda that I wanted to get up here before I forgot all about them, and now, three months later, the details are starting to get a little fuzzy. But hey, most of my stories are full of wild exaggerations and made up details anyway so what does it matter?

Here goes. My own bikey adventures were going to be the setup to a Uganda bike post that went something like this:

(this in itself is going to be a long setup for a short story, but since you all only read this because you're trying to avoid your work I'm sure you won't mind)

I've written before about bikes in Uganda, but since I can't find what I wrote I'll have to give it another go, (though if anyone out there has that email, I'd love to see it again. And I could post it for everyone's enjoyment).

When it comes to two wheeled transport, I really have to say that north americans are punks. In Uganda, as in most other places I've seen in Africa, bicycles are actually transport, and not just for granola eaters or tree huggers or can-no-longer-affrod-to-put-gas-in-my-hummer types. But for everyone and everything. I'm constantly amazed by what can be moved on a bicycle. Here's a brief list of things I've seen being toted around Kampala on two unpowered wheels: a goat, two goats, a goat and a dozen chickens (you tie their feet together and hang them from the basket on the front. they look oddly like a bouquet of flowers), 4 cases of full coke bottles, sacks of maize flour, a few bunches of bananas, a lawn mower, 3 children (this is in addition to the adult who was actually pedaling the bicycle), a bed (this guy was still riding the bike), a coffin (this guy was just pushing), and on and on. I'm still waiting to see a guy carrying a car on a bicycle, cause I know it's been done...

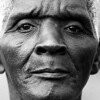

And everyone has the exact same bike, the ever-loved, single speed, solid steel, indestructible Hero bike. Made in India by the millions (at one point at the rate of 19,000 per day), these things are everywhere. Weighs fifty pounds before you put a rider, two goats and a dozen chickens on it. Once you got it loaded up and you get it moving, it's got the inertia of a runaway train. And once you're going, all you've got to stop it are two little rubber pads pushing on your slick steel rims as you hurtle down the road, goat bleating, chickens squawking and the kids on the back screaming "faster! faster!"

Or rather, that's what you get with a new bike. Once the bike has seen a few miles and the little rubber pads on your brakes are worn away, they replace them with little wooden ones. And then it rains. And then you're astride this runaway livestock train with the rain pouring down, hurtling through the deluge, blinded by the drops and you squeeze the brakes and press those little sodden blocks of wood against the equally wet metal rims and the bike actually starts to go faster. You'd do better to just tie a length of rope around one of the chickens and then heave the chicken overboard in the hopes of hooking a tree or something.

Right, so that's the hero bike. So just hold on to that for a moment.

When we were in Uganda, we took a short road trip out to Mbale, a town in Eastern Uganda, towards the Kenyan boarder. As you leave Kampala heading east, you pass through lush, rolling hills that are home to tea and sugar plantations. From a distance, tea plantations look like finely clipped lawns, impossibly green, wrapped around mountains, laid over valleys. When you see people walking along the rows of tea, they look tiny, the closely cropped lawn you were admiring a moment ago reaching almost to their waists.

The Sugar plantations are less exciting, as there really isn't much to see. The sugar cane is so tall that you can't see past it as it lines the road, looking more of less like swampy grass. And while the tea is picked by hand and carried in baskets by the miniature workers, the sugar is hacked down, loaded into huge trailers and then pulled by tractors along the highway to the large sugar refineries. The trailers are open, built like giant baskets, so when they're filled the sugar cane sticks out everywhere, making the trailers look like giant bushes rolling down the road. And it's these tractors and trailers that make up the other part of this little story.

Along one little stretch, the road to Mbale passes through a small island of national forest that straddles a valley, bordered on both sides by sugar cane. The tractors on the far side of the forest are loaded up, driven into the forest, race at obscene speeds down to the bottom of the valley and then crawl slowly back up the other side and on to the refinery. And a lot of the workers that cut sugar cane ride their bikes to work.

So here we are, in a car racing back towards Kampala, just starting to head down into the forest. The car is driven by our friend Billy Francis who tends to drive his car on the faster side (he's been complaining that we're making him keep it under 140km/h). I wasn't actually watching the speedometer as we came up on the sugar cane tractor, but I would have guessed we were going about 100 or 110. The road here is 4 lanes and we were ever so slowly passing this tractor being pushed to the bottom by his fully loaded trailer (they really race to the bottom). Right behind the trailer, less then a bike length for the bouncing stalks of sugar cane was a guy on a hero bike. Drafting behind the trailer at what must have been close to 90km/h, his hat held between his teeth, his face tight, squinting to keep the flying bits of leaves and canes from blinding him, racing, racing down this hill. I'm sure he could have set those little wooden pads on fire.